When the social order of our culture changes within a matter of years and not decades, the Church must deal with the difficulty of orthodoxy in a shifting paradigm. For many, this is a simple matter. Either you are part of the change or you are part of the barriers to that change, depending on your degree of liberalism or conservatism. But how you navigate change matters.

We’ve not done a good job of moving forward to new things. Too often, as a Church, we’ve made the mistake of vilifying the past. We’ve made the mistake of trying to rewrite our history, our traditions, and even our Scripture to follow our new ideas.

A retired pastor breaks the rules of our denomination. A retired Bishop defies the Book of Discipline. A group of pastors seek justice for a same-sex couple by defying a covenant en masse, making it harder for their conference to discipline such a large number of pastors. If removed from their appointments, who would fill their pulpits?

All are claiming that their cause is right and just, and that the rules no longer apply. But we cannot so callously cast aside thousands of years of Scriptural authority, Church law, and, yes, even time-honored tradition.

How does one address the both/and nature of this conversation?

A Devotional Thought

This week, I ate a wonderful meal with some of my favorite people in the world. I was with the Schwab Grace Group, and we were treated to a devotional by our pastor emeritus (no, it’s not official, but, yes, it means something to me) Dr. Benny Hopper. Benny’s devotional opened with a hymn, Come Ye Thankful People Come.

Come, ye thankful people, come, raise the song of harvest home;

all is safely gathered in, ere the winter storms begin.

God our Maker doth provide for our wants to be supplied;

come to God’s own temple, come, raise the song of harvest home.

And then Benny reminded us that our lives are ever-changing. He recounted his first path, that of a young man who wanted to play basketball while studying to become an ag-teacher. God changed that in a series of sleepless nights, and Benny became a pastor — and a darned good one, too.

That wasn’t the end of the changes. He’s seen the world move on, and not without some confusion and disorientation. The thing that struck me most about Benny’s sharing was that his point wasn’t “all this change is bad,” but “all this change is hard to take.” Most clearly, he demonstrated that the good old days were in fact quite good in a number of ways. We do have to admit that those days were better for some than for others, and that for a significant number of people, there were horrible, terrifying days. But there is no denying that a simpler time has been left behind.

The reason his point was so clear to me was because he painted a wonderful picture of days gone by. Benny remembered a time when neighbors knew one another and community was not just something we talked about, but something many people experienced. And I’m grateful for his sharing.

I wonder sometimes if we could recapture some of that sense of community without sacrificing the ground we’ve gained in equal rights for women and for minorities. Ruminations like this can pose difficult questions for those who favor orthodoxy at all costs.

The Difficulty of Orthodoxy

A conversation just a day or two later brought Benny’s words full circle. I was speaking to a co-worker about the emotional burdens that come back around at the holidays. We’ve all lost family to death or distance, and the holidays can be an emotionally charged time as a result. Many of us miss those days, and the warm emotions that go with it. Others are fleeing those days because their experience of it was anything but warm and cozy. Either way, the ending of the year can be tough because of all the memories.

That got me thinking about the massive changes wrought in those days. Those who came through the 60’s and 70’s have experienced a cultural upheaval and disillusionment that is hard enough to deal with once in a lifetime. To see their hesitation to embrace the new digital culture is to remember that they already made one major change in their life. To see their hesitation to break with the past on a number of issues is to recall that they may well have given all they have to give.

And so there follows a cry for orthodoxy. There is a rally to things that seemed unchangeable just a few decades ago. There is a dire fear of things that are new and different, especially things that were considered evil less than a lifetime ago. While it might not be something that we can justify, we should at least be aware that forcing change can hurt just as resisting change has.

The hurting caused by change gets lost when we start hurling epithets of “hate.” I would challenge my brothers and sisters to consider carefully the feelings of those they casually label “homophobic” or “hate-mongerer” when the phobia they have is not of homosexuals, but of change in general. I’ve made those mistakes myself, casting doubt upon the authenticity of a person’s beliefs when they did not see my point in favor of change for what I thought was “the better.” And that’s wrong.

For many, orthodoxy is a retreat to a safe place. Often it is a retreat to a strong place. But orthodoxy must be able to hold its own in a conversation with Christ about the true nature of Kingdom. And orthodoxy must know when to surrender the high ground in favor of God-honoring change for the better.

In a Shifting Paradigm

As much as we would like to declare victory as of the 1960’s and claim that things finally became “just right,” we cannot. Injustices still prevail, often within the very structures that inherited the mantle of Christ, namely the Church. How can this be?

John announced that Jesus was doing a new thing, reminiscent of Isaiah’s prophecy. And while our hearts may be tied to the safety and comfort of the past, the very message of the Gospel recognizes that new ideas become old ideas and charismatic leaders are replaced with institutions and cumbersome structures that become more concerned with self-preservation than the practice of the original ideas. Max Weber called this the “routinization of charisma.” And the charismatic changes that sweep through stale institutions must be repeated as the resilience of the group wanes and its culture becomes stale and rigid.

In other words, the paradigm shifts.

But a shifting paradigm doesn’t mean that anything goes. We still must answer questions of authenticity. We still have a responsibility to maintain the integrity of the Gospel. But the conversation has been stunted. We are having trouble framing the conversation.

In our church, we have a hard time creating the space for that conversation. And when we do, we often have a hard time with matters that have been covered. For example, a colleague in Nashville, Michael Williams, recently posted on his blog a simple question.

“Since LGBT folk are “people of sacred worth” according to the UM Discipline why would we choose to welcome them to take part in our two sacraments and not allow them to be married or ordained, two rituals that are not sacraments?”

I respect Michael’s work and his theology, but this is a question asked and answered: Sacraments are a means of grace available to all. Marriage and ordination are sacred covenants and require a commitment to certain standards. We examine the ordinands and subject our potential pastors to rigorous testing. We counsel those engaged to be married (if we are faithful to the pastoral task). And we verify their commitment to certain standards.

The question that arrives next is, “Are all of those standards still valid?”

That is the question that very few are approaching. We are rushing to answer “Were they ever valid?” and “Can’t you see that we don’t like these standards?” and even, “Who are you to decide for me what a standard is?”

Failed Arguments

We can’t seem to get to the point because we have an inability to frame this conversation as United Methodists. We cannot seem to agree on the nature of sin. We cannot come to agreement on a definition of the homosexual act that states that it is sin. We often cannot agree on the authority of Scripture in this matter. And we confuse the nature of sacrament with orders and vows.

We also have a nasty habit of using eisegesis rather than exegesis to interpret Scripture; that is to say, instead of drawing conclusions from the process of examining Scripture and its context, we inflict our context upon the reading of Scripture, interpreting it in the way that places a more favorable light upon our own positions.

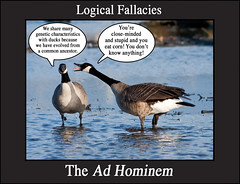

I’ve seen more logical fallacies in the past five years than in the fifteen years prior. Incidentally, Michael’s fallacy is known as “compositional/divisional fallacy,” and occurs when one assumes that one part of something (our sacramental rituals) has to be applied to all (rituals, like marriage and ordination), or other, parts of it; or that the whole must apply to its parts. Straw men, slippery slopes, null arguments, and many, many more have been applied to our conversation, indicating that we are deciding our positions and then reverberating the echo chamber.

The ad hominem attacks the opponent: “Oh, you disagree, so you must hate me.”

The appeal to nature argues that because something is ‘natural’ it is therefore valid, justified, inevitable, good or ideal. “Multiple species in nature are homosexual in addition to humans.” Or, from the other camp, “Homosexuality is an unnatural act.”

Anecdotal arguments use a personal experience or an isolated example instead of a sound argument or compelling evidence. This is evident in the isolated historical accounts and the modern stories of emotionally charged experiences, which gives way to the emotional appeal.

What is the Alternative?

I’ve often been accused of a logical fallacy of my own. It’s called the Middle Ground and claims that a compromise, or middle point, between two extremes must be the truth. But if you listen carefully, I’m not claiming that at all. I categorically deny Scriptural support of homosexuality. Though there are some general statements affirming love and grace, as there should be, there is no Scriptural evidence that the edicts changed.

But hear this carefully: I also categorically reject the notion that God is limited to the pages of Scripture. The Bible is not my God, no matter how much value I place on the words of Scripture.

There is not much in the way of Scriptural support for the practice of homosexuality. And there’s even less in the Book of Discipline for such an interpretation, if any.

But we are neglecting the option for God to do “a new thing.” As with Peter’s vision on the roof of Simon the Tanner’s home, God reserves the right to withdraw some rules when the time is right.

And it’s not just kosher laws about food preparation and actions that make a person clean and unclean. Gentiles before Christ? Circumcision required to convert. Gentiles after Christ (and Peter and Paul duking it out over circumcision)? Not required. Something changed.

If this is the case, we should be looking for a prophetic word, not the magical rearrangement of letters on the page to suddenly stop holding a meaning that they have held for thousands of years. For our denomination to carry out a sweeping change, a paradigmatic shift that is of God will not happen by rewriting our Scriptures, rewriting history, or deflating our traditions. We will have to acknowledge that such was the rule, such was the will of God for a time; but perhaps the time is drawing to a close — or has already passed and we are currently living under outdated standards.

The framing of this conversation must be set in terms of authentic, prophetic words, and there is precious little of that.

Adam Hamilton and Mike Slaughter have encouraged the denomination to make an effort to communicate. Their effort consisted of a motion to acknowledge our differences and admit that we disagree, but the motion was cast aside at the last General Conference. Adam’s book, “When Christians Get it Wrong,” also makes some inroads towards a reframing of this conversation that would at least bring us back into being as a conversing community.

So I call upon my brothers and sisters to reframe this conversation. Stop the theological gymnastics. Lay aside the eisegetical practices. Abandon the vain efforts to point to historical aberrations and pocketed outposts of counter-culture as some sort of forgotten standard.

I have not been given a prophetic word. But if you have, step to the forefront and proclaim the gospel without guile and without subterfuge. If God is doing a new thing, we not only have an opportunity to say so, we have a responsibility.

Joey,this is a profoundly excellent post and analysis. If I may be so bold, I cite two of mine. First is an op-ed I had in the Wall Street Journal back in 2004, “Save marriage? It’s too Late.”

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB122721519267045365

Second is my entirely secular argument on same-sex marriage, http://pastordonblog.blogspot.com/2010/08/what-makes-marriage-marriage.html