In the first post in this series, I shared my early understanding of the Civil War and the picture of history that had been painted for me. In this post, I’ll share some of the things that I found when I moved out of the history books and into the actual records and documents that are there for the reading. This is the second post in a four-part series.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three

Finding Historical Accuracy

Those confederate hats I liked so much went away pretty quickly after I discovered the Lost Cause narrative. The big picture came together as I realized that the chapters on the Civil War and Reconstruction didn’t match up with the preceding chapters on the national sin of slavery. My heroes were a facade. My “memories” of confederate ancestors were tarnished and even made up in some cases.

And then it got worse.

I discovered primary source documents. These documents weren’t offered to school children in the 1980’s, probably because of their blatant and unapologetically racist tone. Remember, desegregation meant that children from predominantly black neighborhoods sat side by side with kids from predominantly white neighborhoods. I have no doubt that school boards decided not to put some of these documents in those southern classrooms for the simple sake of maintaining the peace.

[bctt tweet=”The biggest problem posed by the primary documents is that none of them support the Lost Cause narrative.” username=”revjoeyreed”]

The biggest problem is that none of the primary documents support the Lost Cause narrative. And it’s not even a matter of trying to puzzle out their meaning. These documents are straightforward. These documents come right to the point. And they were buried in history, rarely, if ever, a part of the historical conversation.

How could this happen? I did a little more digging. The conspiracy to withhold this information goes far beyond the efforts of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. I learned later that our sense of American Nationalism is very closely tied to the Lost Cause narrative. Burying these documents was in the nation’s “best interests” at the time. Why? Because many felt that the Lost Cause Narrative would allow traitors and seditionists to become respectable members of society again. More importantly, it allowed entire families to avoid guilt and shame. In short, it hid the dark stain of slavery from the story of the Civil War. But at what cost?

[bctt tweet=”When I first found these documents, it was like discovering the Lost Ark of the Covenant.” username=”revjoeyreed”]

When I first found these documents, it was like discovering the Lost Ark of the Covenant. It felt like these documents had been buried and lost to history. And, in many ways, they have. Before the internet, they were tucked away in libraries. And when the internet came along, the documents seemed to multiply. I’ve linked to some of them below.

Articles of Secession

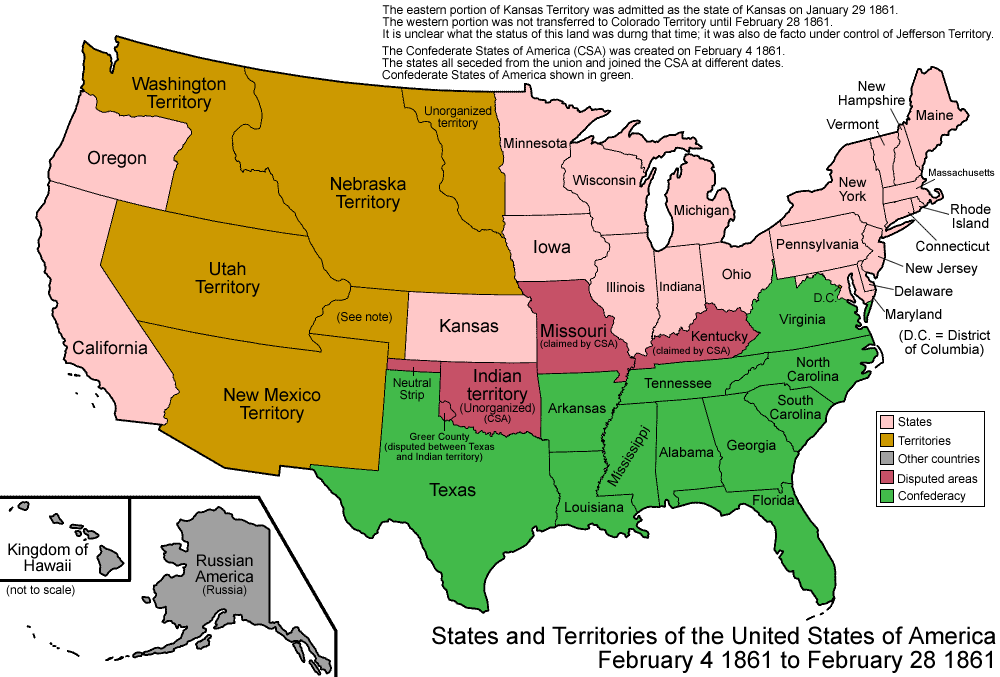

The primary documents which caused me the most revulsion and historical whiplash, if you will, were the articles of secession submitted by states like Texas, South Carolina, and Georgia. Keep in mind that these are not the ordinances of secession. Those are simple documents that were submitted or recorded that simply broke ties with the United States. The documents listed below are the longer, more detailed reasonings for the ordinance itself. Each declaration spoke directly to the issues surrounding slavery and the admission of non-slave states to the Union.

I had never given thought to the idea that states submitted documents to secede. Like everyone else who is even remotely interested in history, I knew about the Declaration of Independence. So, upon consideration, it makes sense for a state to list its collective grievances as it left the Union.

I wasn’t prepared for the strident tone. I wasn’t prepared for the seething hatred. I wasn’t prepared for the clear statement of white supremacy. Of course, I had already cast doubt upon the romantic picture painted by the Lost Cause narrative. But these documents are historical in their tone. These were statements of sentiment on behalf of entire states. And, together, they represented an entire region dedicated to the preservation of their way of life. And that way of life, they clearly claimed, was based on slavery.

[bctt tweet=”I wasn’t prepared for the strident tone. I wasn’t prepared for the seething hatred.” username=”revjoeyreed”]

Georgia

The second sentence of the Georgia declaration reads, “For the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.” The next 20 sentences list the specific things that have disrupted the institution of Slavery, each a cause for Georgia’s secession.

Mississippi

Mississippi follows suit. Here’s its second sentence: ” Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery– the greatest material interest of the world.” Mississippi also complained that the federal government “advocat[ed] negro equality, socially and politically, and promotes insurrection and incendiarism in our midst.” That’s pretty clear wording, I might add.

South Carolina

Now, South Carolina had a historical bone to pick. They seem to take exception to the fact that they were drawn into a new nation with less power than they had before they were united with other states. But they did get around to slavery, noting “The Constitution of the United States, in its fourth Article, provides as follows: “No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up, on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.”

Texas

Texas didn’t tarry quite so long. They hit on slavery in the third paragraph:

Texas abandoned her separate national existence and consented to become one of the Confederated Union to promote her welfare, insure domestic tranquility and secure more substantially the blessings of peace and liberty to her people. She was received into the confederacy with her own constitution, under the guarantee of the federal constitution and the compact of annexation, that she should enjoy these blessings. She was received as a commonwealth holding, maintaining and protecting the institution known as negro slavery– the servitude of the African to the white race within her limits– a relation that had existed from the first settlement of her wilderness by the white race, and which her people intended should exist in all future time.

Virginia

Virginia was short and to the point in their statement, but clearly identified the reasoning: The federal government had injured the slave-holding states’ ability to trade in commerce through the anti-slavery actions taken by Congress and others.

Other Primary Source Documents

These aren’t the only historical documents of the time, obviously. But they are representative of the secessionist notions that were prevalent in the South. Many of the links above will take you to pages and pages of those historical documents. And in most cases, they will, in turn, link you to even more of those documents.

These are not the musings of historians. These are not the result of a favorable interpretation. These are the writings of men who thought themselves to be on the right side of history, but were sadly mistaken.

[bctt tweet=”I wasn’t in school to learn all there is to know. I was in school to learn how to learn. ” username=”revjoeyreed”]

Without these clues to the underlying causes of the Civil War, we would be left with the Hollywood treatments of a romantic mythology. With the discovery of these types of documents, I learned that my education was not complete and was never intended to be. I wasn’t in school to learn all there is to know. I was in school to learn how to learn. I was in school to learn to think and discover for myself, with all of the skills and abilities my educators could cram into me for that job.

And what I was learning about history was that the parts I loved best weren’t the whole truth. And the darkness behind the Southern facade was going to grow deeper.

This is the second post in a four-part series.

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

I think your comment about the seething hatred is interesting and right on target. Once we hate someone, we interpret everything we see to be in support of that hatred. The reason for secession was that the south hated the north. And the north hated the south. If they were married, divorce court would have granted a separation. That’s what the south wanted. But northern pride and greed prevented that obvious solution.

Allowing the nation to divide over something so morally bankrupt as slavery would have been a tragedy, and not just in hindsight. The north may have had financial motives, but national pride may have served us well all these years later.

Lincoln discussed the divorce analogy in his first inaugural address:

Physically speaking, we cannot separate. We cannot remove our

respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall

between them. A husband and wife may be divorced, and go out of the

presence, and beyond the reach of each other; but the different parts

of our country cannot do this. They cannot but remain face to face;

and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between

them. Is it possible then to make that intercourse more advantageous

or more satisfactory, after separation than before? Can aliens make

treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more

faithfully enforced between aliens, than laws can among friends?

I don’t think you interpreted the Virginia declaration correctly. On April 4, Virginia voted 2:1 against secession. Then on April 15 came Lincoln’s intention to invade the South (necessarily by virtue of geography) through Virginia and North Carolina and Lincoln did this illegally without a declaration of war by Congress. Two days later, Virginia voted 2:1 for secession citing “Federal Government having perverted said powers, not only to the injury of the people of Virginia, but to the oppression of the Southern slaveholding States, “. I think the perversion reference was to an illegal use of one state’s militia to invade another state.

Thanks, Matt.

I will reread the secession document. I’m not sure that it will delete the racism that undergirded Virginia sentiments toward the North, but it may well dilute the notion that racism and slavery were the driving forces for their secession.

Thanks again for the heads-up.

In 1861 the majority of neither side understood slavery to be morally bankrupt. The love of money is the root of all evil (1 Timothy 6:10) and, in my opinion, that love of money clouded the judgment of both north and south. Again, in my opinion, one of the most important lessons of the Civil War is how incredibly good we humans are at self justification.

National pride is one thing, but to lose reason because of it can lead to devastating consequences. The hysteria of “they dared fire on our flag/troops/ships” has led to at least four unjust wars – Mexican American (Mexicans fired on US scouting party inside disputed territory; Spanish American with it’s yellow journalism and the provocation of putting the battleship Maine in Havana harbor; Civil War by instigating the bombardment of Ft. Sumter and the Vietnam war by hyping up a very minor incident in the gulf of Tonkin.

Here is a primary document that helps illustrate the close connection between northern financial interests and southern slavery: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/mayor-woods-recommendation-of-the-secession-of-new-york-city/

It is a letter written in January of 1861 from Mayor Fernando Wood of New York City recommending that NYC secede with South Carolina. If slavery is Dr. Frankenstein’s monster then the bankers of Wall Street along with the US government was Dr. Frankenstein himself. In my opinion, the love of money, as actuated in a fully integrated north and south economic system, was responsible for slavery.