These four questions round out the scholarly method used by N.T. Wright to examine some of the deepest questions of our faith. Wright has examined Jesus, Paul, the notion of the Kingdom of Heaven, and taken on the most confusing issues of our beliefs, including atonement, the Resurrection, and many more.

With apologies to my favorite theologian, I am taking up his method to think a little about the future of the United Methodist Church. If you are just joining the conversation, I encourage you to read the previous posts in this series.

– A Vision for the Future: Premise (1/5)

– A Vision for the Future: Story and Symbol (2/5)

– A Vision for the Future: Praxis (3/5)

Wright supposes that, by defining our Story and Symbols, we can then set them in motion and learn from their Praxis, or movement in the world. Most Methodist seminarians know the stories and symbols by heart — and several have even heard of the Methodist Praxis.

But when I set out on this journey, I did not realize the incredible gap between the Church of today and the Methodist Story, Symbols, and Praxis of centuries and decades past. I knew that we had lost some of our nerve. And we’ve abandoned a few principles along the way. However, the problem goes far deeper than I imagined.

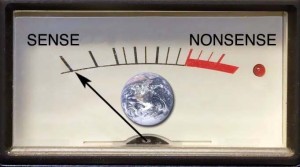

I am becoming more and more convinced that we are fast becoming unMethodist. Our thinking is polluted by talking heads and running mouths on Cable News networks and nationwide talk radio outlets. Our theology is widely unknown and broadly unkempt.

Yes, there are bastions of faith and method. There are strongholds of belief where the Quadrilateral is a tool and not a geometry problem. A quick search on Google will bear this out. But I would imagine that there are far too many churches on any given Sunday that would look more like Jay-walkers than Wesleyan Christ-followers when asked questions about the doctrine and standards of our faith.

How has this happened? I do not know. But I think I know how it perpetuates. And the answer comes from N.T. Wright’s four questions, asked in light of our Story, our Symbols, and our Praxis

Who Are We?

First, let me qualify this question. I am speaking of the Western context of the United Methodist Church.

American culture has evolved, in many key ways, from a principled nation to a nation of appetites. Our principled stands have not evaporated. They have been replaced with adopted notions and talking points. We no longer maintain our beliefs because we understand them.

Our opinions are mercurial. Our causes are shallow. Celebrities garner more influence than clergy when it comes to rallying the people for the sake of an issue. Even dead celebrities can rally a group quicker than most living pastors.

Our opinions are mercurial. Our causes are shallow. Celebrities garner more influence than clergy when it comes to rallying the people for the sake of an issue. Even dead celebrities can rally a group quicker than most living pastors.

We are a people who tend towards being told what to do and what to think.

In a Pew Forum Survey released in 2010, the indicators demonstrated that Christians have a general inability to rationally discuss our faith and answer questions about what we believe and why we believe it.

When asked to explain this phenomenon, Rev. Adam Hamilton answered

“I think that what happens for many Christians is, they accept their particular faith, they accept it to be true and they stop examining it. Consequently, because it’s already accepted to be true, they don’t examine other people’s faiths. … That, I think, is not healthy for a person of any faith.”

Indeed. I would add that it goes deeper. We, as Americans, have relinquished the responsibility for forming our opinions. We now seem to merely adopt our ideas, joining bandwagons without the ability to add a single note to the tune.

We are no longer the processing thinkers that we once were.

Where Are We?

We live in a land of consumers. Our economic production capabilities have been reduced, but seem to be back on the rise. Economist, professional and otherwise, are calling for increased manufacturing capability to correct our economy.

I think this inability to produce extends even deeper. Our culture has become incapable of producing, in large numbers, people who are able to think and reason for themselves. Americans, to a deplorable degree, seem willing for a surrogate thinker to provide them with their political opinions, their social mores, and their spiritual beliefs.

The classical education that was once taught in colleges, schools, cabins, and courthouses across our nation is no longer the norm. When Jefferson and Madison wrote their political opinions, there were lines and lines of proofs, logically arrayed and presented for the people to consume and digest. In short, a patriot was formerly known for his or her citizenship. And I do not mean “right to live here.” That is another blog post entirely.

The classical education that was once taught in colleges, schools, cabins, and courthouses across our nation is no longer the norm. When Jefferson and Madison wrote their political opinions, there were lines and lines of proofs, logically arrayed and presented for the people to consume and digest. In short, a patriot was formerly known for his or her citizenship. And I do not mean “right to live here.” That is another blog post entirely.

What I mean by “citizen” runs to a deeper sense of responsibility, a greater sense of reliability and capability. In short, a citizen is someone who can and will contribute to society. Those are difficult to find. This is where we are.

The same could be said of our Wesleyan discipleship. The impact of the Methodist movement was simple in so many ways: Clergy taught the laity how to read Scripture for themselves, how to pray for themselves, and how to govern themselves as a local congregation.

What is the Problem?

I think you’ll be struck by this description of expectations from a class of laymen and women, from the Methodist Quarterly Review of a century ago or more. The expectation here demonstrates a capability that we cannot find universally in the modern clergy, much less laity:

He was not satisfied until each member could for himself prove from Scripture every doctrine he professed and quote from Scripture the warrant for each promise on the fulfilment of which he relied.

The brother who has had charge of this class since Father Reeves’s decease fully bears out the statement that the members generally are well grounded in Scriptural proof of all our doctrines and can give in the terms of Scripture a reason for the hope that is in them.

Today, men and women are more likely to think in soundbites and vote in herds. We divide ourselves based on a few catch-phrases and the political ideologues who masquerade as entertainers and entertainers who masquerade as political ideologues.

We do the same when we shortcut our discipleship, or more to the point, our spiritual beliefs.

We do the same when we shortcut our discipleship, or more to the point, our spiritual beliefs.

The problem, more simply stated, is that we are no longer self-reproducing citizens or disciples. To focus upon our Methodist problem, our members are no longer generally capable of reproducing their faith in another human being. Methodists in North America demonstrate a marked departure from discipleship as it was practiced in the last century.

Today, Methodists are calling for major changes to our beliefs without considered reflection. I do not oppose change. If a law or doctrine is wrong, we should protest it. But if we protest it we should have a reason for doing so, and be able to clearly state it in terms that demonstrate fair cause for agreement. But we are under no obligation to agree, despite the wide-spread notion that we must do so or be labeled “bigots” or “heretics.”

Our culture decries any semblance of intolerance to the point that we don’t tolerate intolerance itself. In fact, we are so intolerant of intolerance that we have changed the meaning of tolerance to now say, “I agree with you on every facet of every point.”

Tolerance, as I have said elsewhere, is merely the willingness to coexist with others with whom one disagrees. Let us not confuse the issue of agreement and tolerance!

In issues of church and state, together or separated, our American society has become inarguably petulant on issues that divide the national consciousness. Our arguments, all too often, boil down to “I’m right and you are wrong.”

In issues of church and state, together or separated, our American society has become inarguably petulant on issues that divide the national consciousness. Our arguments, all too often, boil down to “I’m right and you are wrong.”

We protest without purpose because others do so. Conversely, there are those ridicule those who protest because a fraction of the protesters don’t have a rationale for their protest — without bothering to consider that there may be a valid reason held by the majority.

A wide-spread inability to support a theological argument is the base problem with our denomination, made all the more terrifying when it extends to an alarming number of the people who are making the decisions that will determine our future.

In short, our culture is producing people who follow the loudest voice, not the one that speaks with the most rational tone. Our culture is guided by the flash of our entertainment industry (Why is Justin Bieber an authority on anything?) rather than the authority of sound principles, rational thinking, and a logical methodology.

Conclusions

I have rarely asked anyone to convince me that they were right and I was wrong without a willingness to hear their points and judge their individual merits. Many heartfelt and passionate appeals have fallen short of convincing me simply because the debate ran toward the maudlin rather than standing on the merit of scholarship, or rational thought, or that rare cultural beast known as logic.

The question of who we are is tightly wound in the fabric of where we are living. And the two taken together point toward a culture that is swaying in the breeze of public opinion, popular notions, and leaders who make emotional appeals to the base with battle-cries and slogans.

The question of who we are is tightly wound in the fabric of where we are living. And the two taken together point toward a culture that is swaying in the breeze of public opinion, popular notions, and leaders who make emotional appeals to the base with battle-cries and slogans.

I am open to change. In fact, I’ve long been a proponent for change for decades now. But I find myself standing between those who want change because it feels good and they want it, and those who resist change in the form of renewal because it asks so much of them and they don’t want it. We must change, indeed. But not in the ways that so many are supporting without logic, without reason, and without rational consideration of their intention.

The United Methodist Church is well on its way to becoming unMethodist. That said, we must add the words of Ted Campbell. “The end or goal of Methodist teaching is not the advancement of Methodism. Our heritage has been used by God for a much greater end: the coming of God’s reign or kingdom.” [Ted Campbell, Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials, p. 33]

We are in danger of abandoning the very methods that made our denomination so incredibly capable of ushering in the Kingdom. Having stated the problem in this way, perhaps the solutions may begin to resolve themselves with some clarity.

—

Next week, I’ll try to sum this all up by answering the last question: What is the Solution? I look forward to your comments and suggestions for how to do so while maintaining the best standards for thinking through this difficult issue.

Recent Comments